These have been dark times for many musicians. As the Covid-19 quarantine continues to close our favorite stages and end our concert seasons, there are many days when our arts ecosystem feels unhealthy at best and under attack at worst. However, we’ve also all seen this glimmer of sheer beauty shining through this time: the global and spontaneous response of musicians to help, to inspire, and collectively, to rise. Whether it’s concert livestreams, workshops to help folks trying to develop new skills, practice groups to lift each other up, gratis private lessons to help students in need, or just an encouraging “you’ve got this!”, there rose among musicians everywhere a response to heal this universal sense of woundedness in our community.

There is, and always has been, an economy of generosity in our field – the little movements toward good often accompanied by a lot of love and no expectation of recognition. Musicians have a constant desire to contribute, to be useful, and to help others to the very best of their abilities. All great music shines from lives built on such small kindnesses, especially in days like these.

The Power of Empathy

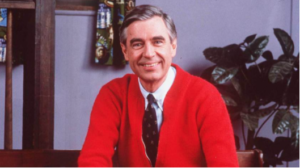

Children’s television series host Fred Rogers (1928 – 2003) gave a commencement address to graduates of Dartmouth College, which was featured in a recent documentary about his life. In it, Rogers shared:

“I’d like to give you all an invisible gift. A gift of a silent minute to think about those who have helped you become who you are today. Some of them may be here right now. Some may be far away. Some, like my astronomy professor, may even be in Heaven. But wherever they are, if they’ve loved you, and encouraged you, and wanted what was best in life for you, they’re right inside yourself. And I feel that you deserve quiet time, on this special occasion, to devote some thought to them. So, let’s just take a minute, in honor of those that have cared about us all along the way. One silent minute.

Whomever you’ve been thinking about, imagine how grateful they must be, that during your silent times, you remember how important they are to you. It’s not the honors and the prizes, and the fancy outsides of life which ultimately nourish our souls. It’s the knowing that we can be trusted. That we never have to fear the truth. That the bedrock of our lives, from which we make our choices, is very good stuff.”

This silent minute brought me immediately to thinking about my teachers. When I was a student, I had immense gratitude for, and a keen awareness of, the incredible wisdom, accomplishments, and patience (so much patience!) of my wonderful teachers. What I didn’t comprehend at the time was that these mentoring relationships were the seeds of cherished friendships that would continue for decades after graduation. It’s a model that I have had the great privilege to carry on now with my own very beloved students. We flutists are so very fortunate to be able to work and forge these wonderful relationships together, whether we are the student or teacher, and to have the opportunity to bring joy, healing, and progress into one another’s lives through this great art of making music.

This silent minute also made me consider a very famous quote by the great poet Maya Angelou:

“I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

There are moments in our modern times, fraught with social media, cancel culture, and politics, when it might seem like empathy is far from people’s minds. Flutist Leone Buyse gave a moving talk about the topic as it relates to teaching at the National Flute Association Convention, which then became an article for the National Flute Association’s Flutist Quarterly (Fall 2017). In it, she wrote about a simple reminder from her parents.

“In my early years, my parents actually taught me about empathy, although I didn’t know that word at the time. Whenever my mother and I went through the checkout line at a store, she would always say, “Be nice to the woman at the cash register because you never know what kind of a day she has been having, and you might help to brighten her mood.” My father often would remind me to think carefully before speaking, so that I wouldn’t make a thoughtless remark that might hurt a friend’s feelings. I’ve now been officially teaching for 50 years. Gradually through the past several decades, I’ve come to believe that our ability to reach students is greatly affected by the degree to which we consciously access and use empathetic skills as we teach.”

Imagine the peace and encouragement that can be brought into students’ often chaotic lives when we as teachers use our words to care for each flutist, to use our focused attention to show that we are fully present in each moment we share with them, and to align our skills to support whatever goals they may design for their lives. These gifts can stay with a student throughout their careers and leave a legacy of care for generations of teachers and performers.

The Foundation of Networking: Generosity

There seems to be a universal disdain for the concept of “networking.” However, effective networking is, in fact, nothing more than creating meaningful friendships. All lasting professional connections are built on trust, an alignment of basic values, and courtesy, again not so different from most friendships. Friendships endure as we extend generosity and care towards one another, but what might this look like in our music profession?

One universally appreciated way to communicate generosity within the field of music is to truly hear and be present as we share performances. In other words, attend concerts with enthusiasm (as many as you possibly can) and immerse yourself in recordings, old and new. Showing appreciation in this way is the quickest path to a musician’s heart. It also brings us into a shared experience with other music-lovers in the audience, kind of like when you meet someone who’s a fan of your favorite band. I must confess that I’m completely baffled by young musicians who feel they are too busy to attend live concerts or who do not make a regular habit of listening to recordings. (I’m only slightly less baffled by flutists who only listen to the music they are practicing.) Sadly, that is truly a lost networking opportunity. We must be committed to becoming great artists, not just great flutists, and the only way to do this is to expose ourselves to great playing. Art captures the imagination of the audience beyond individual disciplines and communicates to a larger shared sense of humanity. It is the thread that connects us with others. What better opportunity for networking could there be?

Networking doesn’t have to mean figuring out ways to be invited to the big table that everyone else wants to be seated at. It can also mean hosting the bountiful dinner yourself and creating space for others to join you. It’s true that visionary people are important to a project, but in my experience, the most important people in any project are those I call the “activators,”. Essentially, these are folks who are effective organizers and story tellers, and here’s why they are so important.

Being an organizer is about assembling and mobilizing a great team and finding those folks whose skills, values, and ambitions align with yours, whether they are in your immediate network or not. We must also remember the importance of diversity, equity and inclusion. Not only is this unquestionably an ethical imperative, but this broadened perspective will yield a greater depth of art and innovation that will elevate any project to its optimal level. Being an organizer is a learned skill. Give it a try, and I guarantee you’ll have your share of failures and mishaps, but through each one, I also guarantee that you’ll learn and become stronger. Have courage and journey onward!

I mention the importance of being a great storyteller; this is different than being a great writer. To me this is comparable to saying, it’s important to be a great artist over being a great flutist. Writing a compelling story is more than technical skill: it’s imagination, it’s clear trajectories and conclusions, and it’s the story arc (timeline) and characters. It’s the backbone of what we do musically, but it is also the key to putting together an effective grant narrative, to communicating with future funders, and of course, to energizing audiences in person, on social media, and beyond. The ability to tell a story in an engaging and compelling way is the key to bringing a project to life, and each project gives you the opportunity to advocate for others to join you along the way.

What would be a useful project for you to bring into your career? An annual seminar that offers your unique approach to helping students prepare for college auditions? A concert series featuring music for flute “plus one” for you and alternating colleagues on any instrument? A flute choir that only plays music by living composers, regularly featuring composers from your area? A podcast that connects great music and great food/wine? The sky is the limit. Creating a new endeavor is innately gratifying to our sense of imagination. It’s worth the effort for you and your network!

Who are the Champions?

Two women have inspired me for years: Marian Anderson (1897 – 1933) and Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933 – 2020). Both faced cultures of bigotry, and both rose to battle against those very forces in ways that changed the course of history. Indeed, they were champions in their fields, but with humility, they were also quick to acknowledge those who championed them along the way.

Marian Anderson

“I used to say and I used to think, and maybe I still do, that if from our concerts or if from what people know about me, that I had left something which at one time or another might have healed a wound, or lifted a lid, or let fly some things which we have felt many people needed to have happen for them… I haven’t set out to change the world in any way because I knew I couldn’t. Whatever I am, it is the culmination of the good will, the help, the understanding, of the many people I met around the world, who have regardless of anything else, saw me as I am, and not trying to be somebody else.” Marian Anderson

Among the most celebrated voices in American history, the great contralto Marian Anderson’s life and career faced innumerable barriers in the reality of brutal racism against African-Americans. Her performance at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939 became not only an artistically important rendition of “My Country ‘Tis of Thee…”, but most significantly, it became a critical moment in U.S. history that profoundly impacted and catalyzed the Civil Rights movement.

When we look to influences in Anderson’s life, we recognize the illustrious conductor Arturo Toscanini, who famously told her, “A voice like yours is heard only once every hundred years,” as Anderson’s star swiftly rose in Europe after having been denied opportunities in the U.S. We also see First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who left the Daughters of the American Revolution when the organization refused to allow Anderson to sing at Constitution Hall. Roosevelt opened the door for Anderson’s historic performance at the Lincoln Memorial in front of a crowd of 75,000 and a radio audience.

However, there were others who are unheralded but were equally visionary in recognizing the giftedness of young Marian Anderson. Her first teacher, neighbor Mary Saunders Patterson, taught Anderson for a discounted $1 a lesson and gifted her a dress so that she could attend concerts. Additionally, the accomplished singers at Philadelphia’s Union Baptist Church, Anderson’s family church, recognized her remarkable gift as she began performing with them as a child. They mobilized the congregation to raise funds that covered years of Anderson’s lessons with her second voice teacher, Giuseppi Boghetti.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Supreme Court 1993 – 2020 and well-known opera lover) often shared the account of winning her first clerkship with a descriptive story of the “carrot and stick”. Despite graduating as valedictorian of her class at Columbia Law School, she struggled to find work in a field that was unwelcoming to women. Her Columbia law professor, Gerald Gunther, an important mentor, intervened. He regularly recommended his best students for prestigious clerkships with Judge Edmund Palmieri. Justice Ginsburg recounted that the “carrot” was the promise that Gunther would refer his best male student to Palmieri if Ginsburg didn’t “work out”. The “stick” was that Gunther would never refer a student again if Palmieri didn’t accept her. Unsurprisingly, not only did Justice Ginsburg rise to the occasion, but she was given a second year of her clerkship.

A common objection to Justice Ginsburg as she launched her career extended beyond her being female to the fact that she was also a mother. Yet her marriage to Martin Ginsburg became an enormous source of support for her. In his final letter to his wife, he wrote:

“My dearest Ruth, you are the only person I have loved in my life. Setting aside a bit parents and kids, and their kids. And I have admired and loved you almost since the day we met at Cornell some 56 years ago. What a treat it has been to watch you progress to the very top of the legal world! I will be in Johns Hopkins Medical Center until Friday, June 25th, I believe and between then and now, I shall think hard on my remaining health and life, and consider on balance that the time has come for me to tough it out or to take leave of life because the loss of quality now simply overwhelms. I hope you will support where I come out, but I understand you may not. I will not love you a jot less.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg faced a culture that believed she was intellectually inferior to men and that women, especially mothers, lacked the ambition to meet the demands of a career in law. Marian Anderson battled a culture that denied her rights and dignity, that denied the belief that she possessed the sophistication to present Art songs and navigate multiple languages. Anderson’s voice was among those who mobilized the Civil Rights movement, and Justice Ginsburg was among the most significant advocates for women’s rights in U.S. history. The love, vision, and generosity of those around these remarkable women gave them encouragement and opportunity along the way. Imagine our world without these women and all they’ve contributed throughout their careers, and I’m sure we agree that we can all feel grateful to the many helpers who crossed their paths.

What is our inspiration?

During my professional career, I have often pondered what it means to live out my Christian faith as a professional musician, and I constantly return to a core belief in generosity: God insists upon the care of “the least of these” and for humanity’s common good. Of course, valuing the common good is a belief that’s shared by many faiths, offered in the guiding words of loving parents, and fueled by a basic humanitarian sense of decency.

When we think about the common good for our music field, we return to the importance and beauty of these small gestures of generosity: to teach, to share a good word or new skill, to create or extend an opportunity, to collaborate on an idea, or – most importantly – to lend an ear. There is power as we raise the tide for all ships – when we do what we can with all that we’ve been given – not only for ourselves and the benefit of others, but for the health and enduring strength of our field as a whole.

(Chicago Flute Club Pipeline Magazine, April 2021)